| City/Town: • Little Rock |

| Location Class: • Amusement |

| Built: • 1950 | Abandoned: • 2001 |

| Status: • Demolished |

| Photojournalist: • Ginger Beck |

Table of Contents

The purchase of Gillam Park was authorized by Mayor Horace A. Knowlton and the Little Rock City Council at a meeting on November 22, 1934, with the approval and support of the Little Rock Chamber of Commerce. The purchase addressed two problems. The first was the growing homeless population in the city, which was being fed and sheltered during the Great Depression era by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). The second was the lack of recreational facilities for Little Rock’s black population. Although the city funded six whites-only parks, it provided none for its black population, contravening the established segregation principle to provide “separate but equal” facilities.

At the end of 1935, the city council proposed a bond issue of $15,000 “to purchase, improve and to cover the city’s contribution for the development of the colored park.” The park bond issue was bundled with two other bond issues, one for $468,000 to build the then-segregated downtown Robinson Auditorium, and another for $25,000 to construct and equip a segregated addition to the city library. The bond issue for the black park was added “as sop” to win black support for the white projects and to encourage white voters to support the black park project. All three bonds passed in January 1937.

However, it was not until after World War II that the city turned its attention back to Gillam Park, responding to protests from the black community. The city agreed to issue a bond for $359,000 to pay for the development of black recreational facilities at Gillam Park. In doing so, the city fully expected the bond issue to fail, but at least, it believed, it would show token goodwill. The bond issue went to the voters on February 1, 1949. Then, as the Arkansas State Press, a black newspaper owned by L. C. and Daisy Bates, described it, “The unexpected happened—the bond issue passed and has made the city the acme of deception and the laughing stock of the entire south.” The Arkansas State Press predicted, “It is not going to be spent any time in the near future if there is any way for the present administration to stop it.”

Fifty years ago, on July 2, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. The act tackled segregated education, voting rights, women’s rights and worker’s rights. Its most immediate impact, however, came in ordering the abolition of segregation in all “public accommodations.”

Little Rock was already ahead of the curve in most areas of desegregation. In 1963, it had implemented a program to allow equal use of many public and some private facilities downtown. Jet magazine quoted James Forman, national executive secretary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), saying that Little Rock was “just about the most integrated [city] in the south.”

But Little Rock, as many other places, faced one final hurdle: desegregating public swimming pools. Pools brought African Americans and whites into close and intimate contact more than any other publicly sponsored facility. This in turn touched on the fraught issue of African-American men and white women bathing together in states of undress. And with that came deep-seated white fears of miscegenation.

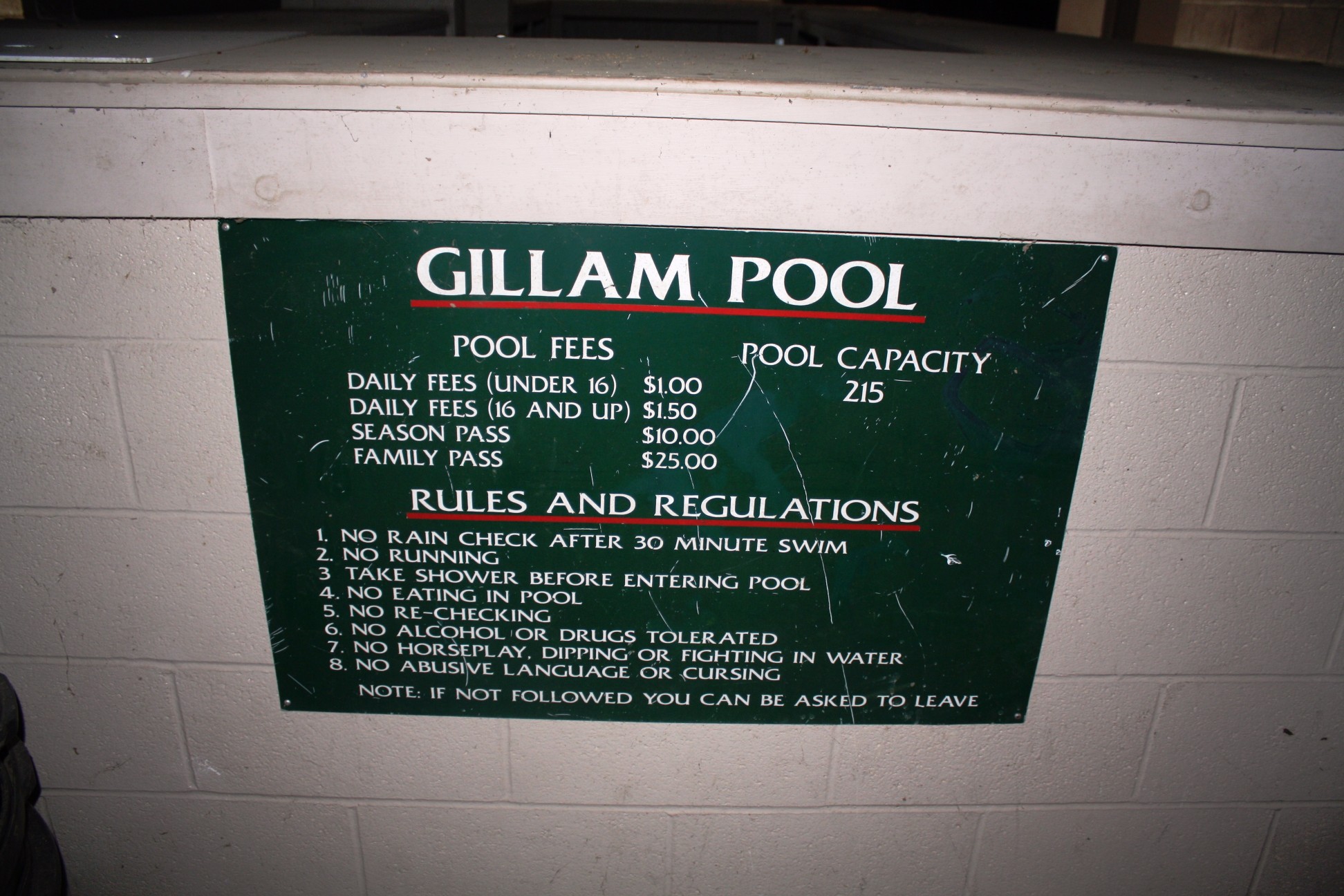

Under the terms of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, the Court required “separate but equal” facilities for blacks. Clearly, Little Rock’s provision of a whites-only pool without any facilities whatsoever for its African-American population violated that requirement. In 1949, the city passed a bond issue for the development of an African-American Gillam Park southeast of the city, which included a swimming pool. The pool opened on Sunday, August 20, 1950.

Less than a year after opening, however, the Gillam Park swimming pool was reported leaking. Attendance was poor. Problems came to a head in July 1954 when Tommy Grigsby, a black boy, drowned in the Gillam Park pool. At the time, the pool was understaffed with lifeguards, and it lacked a respirator that might have saved Grigsby’s life. Its remote location also meant that a doctor and rescue squad could not reach the scene in time to resuscitate him.

J. Curran Conway Pool’s segregation policy was first tested on June 27, 1963, when Dr. Jerry Jewell, president of the Little Rock NAACP branch, and L.C. Bates, Arkansas NAACP field secretary, led a group of four would-be swimmers. “We are still segregated here,” pool manager Leroy Scott told them. After the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Jewell and Bates, along with 15 African-American boys and girls, returned. They were denied entry again. Barely five hours later, Little Rock City Manager Ancil M. Douthit announced that J. Curran Conway Pool and Gillam Park Pool “would be closed or sold to private owners” to avoid integration.

The following Monday, both J. Curran Conway Pool and Gillam Park Pool were closed and drained. Douthit claimed that the city was “close to selling” them. He advised the roughly 300 season ticket holders that refunds would be available from the front desk of the pool between 9:30 a.m. and 6 p.m. on Tuesday and Wednesday. Since approximately one-fifth of the season had already elapsed, the city gave a $4 refund on the $5 season tickets.

Things stayed the same until mid-April 1965 as the beginning of the new swimming season approached. A campaign to re-open the pools on an integrated basis grew. Ahead of the next scheduled city board of directors meeting, local SNCC activists collected 1,300 signatures in a petition to desegregate city swimming pools. At the meeting on June 2, 1965, City Manager Douthit announced that the swimming pools would open on an integrated basis “as soon as … physically able.” Developments in the courts after the 1964 Civil Rights Act had made it clear that the city could no longer legally evade desegregation.

On Monday, June 14, the Gillam Park Pool was the first to re-open in drizzling rain. Only a small group of African Americans and no whites used it. Meanwhile, engineers over at J. Conway Curran Pool battled with water pump and motor repairs, along with a cracked pipe. Business was slow when the pool reopened the following Monday. About two dozen whites, mostly children accompanied by their mothers, were ready and waiting to swim. The first three African Americans arrived that afternoon at 1:30 p.m. About half an hour before closing, at 5:30 p.m., there had been 210 swimmers that day, 22 of them African-American. Gillam Park Pool’s numbers had increased slowly since opening the week before and a few whites had swum there.

Gillam Park Pool closed in 2001 and has been derelict since. Only two new public swimming pools have been constructed since 1965, both, tellingly, in areas of high African-American residence, which virtually guarantees predominantly African-American usage. East Little Rock Pool opened at the East Little Rock Community Complex in 1972. It closed in 2002. Southwest Community Center Pool opened in 1998 and remains in operation. The Southwest Little Rock area witnessed a dramatic shift in population in the period before the pool was built, with 9,000 whites leaving and 6,200 nonwhites arriving in the decade between 1982 and 1992. In the same decade, the population in the almost exclusively white far west of Little Rock, where the number of private pools has proliferated, leapt from 14,874 to 25,930.

Fifty years after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Little Rock perfectly fits the bill as described in Atlanta by historian Kevin Cruse: “In the end, court-ordered desegregation of public spaces brought about not actual racial integration, but instead a new division in which the public world was increasingly abandoned to blacks and a new private one was created for whites.”

In the twenty-first century, Gillam Park is managed by Audubon Arkansas, which has its Little Rock Audubon Center nearby. The park contains one of the few exposed igneous rock clusters of nepheline syenite in the world, with an endangered and federally protected plant, the small-headed pipewort, growing on top of the cluster. One of the state’s oldest groups of white oak trees also stands on the land.

Gallery Below

Sources:

https://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/swimming-against-the-tide-of-desegregation-in-little-rock/Content?oid=3199765

http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=2639

If you wish to support our current and future work, please consider making a donation or purchasing one of our many books. Any and all donations are appreciated.

Donate to our cause Check out our books!

I moved to granite mountain around 2005 to 2011 and grew up there a little bit, me and my friends always wondered what was passed the closed gates and they had a event called “granite mountain day” and they used to bring their cool cars and drive pass the gate and have a good time. I remember me and my friends riding our bikes to look at the pool and it was a scary adventure especially riding our bikes through the street trail basically in the middle of the woods lol and at the time I was maybe 6 or… Read more »

My parents frequented the pool and park in their younger years. Both are in their 60s now. Fascinating to learn about the park and view photos of it as I’ve never had the chance to see it with my own eyes, only heard the stories! Thank you.

A person suggested a putting a bladder in the cistern. That sounds like a great idea;however, if the cypress were to become dry the cistern would fall apart. Our next door neighbor allowed his cistern to fall into great disrepair by not keeping water in his. The cypress dried to the extent that the metal bands holding them fell off and then, the cypress planks began to separate.

Thank you. It's very interesting to learn something new about such places. Thanks to photos and history, I seemed to have visited there myself.

thank you Margaret!

awesome!